Some days, he labored over hand-drawn animations; on others, he made music or organized shows or film screenings at Glob, the venue in a Brighton Boulevard warehouse where he lived, a remnant of the trendy RiNo neighborhood’s industrial past.

That afternoon, he planned to record a friend singing. But thirty minutes before the vocalist was slated to arrive at Glob, Golter heard a pounding at the door. Minutes later, there was another knock, this one at Rhinoceropolis, the adjacent venue that was a nationally renowned playground for experimental culture.

Golter opened Glob's door: Standing outside were inspectors with the Denver Fire Department, asking to come in. Golter's first response was to shut the door and lock it, but then he changed his mind. Why not get the inevitable over with?

He'd been expecting a visit. Days before, on December 2, 2016, a fire had broken out at Ghost Ship, a DIY live-work arts space in Oakland, California, and 36 people had died. After the Ghost Ship fire, cities across the country were put on notice: Were they paying enough attention to DIY arts spaces? Was Oakland, at least in part, responsible for the tragedy? There had been reports of crackdowns on other arts spots around the nation.

Fire inspectors had visited Glob and Rhinoceropolis in the past, though, and had always given the spaces the okay after a couple of issues were addressed; Golter was expecting more of the same this round. He assumed they’d walk in, cite the spaces for a few code violations and then ultimately allow the venues to continue operating. Unlike Ghost Ship, which was basically a two-story tinderbox full of flammable objects, Glob and Rhinoceropolis were located in cinder-block warehouses that were about as fire-resistant as buildings can be.

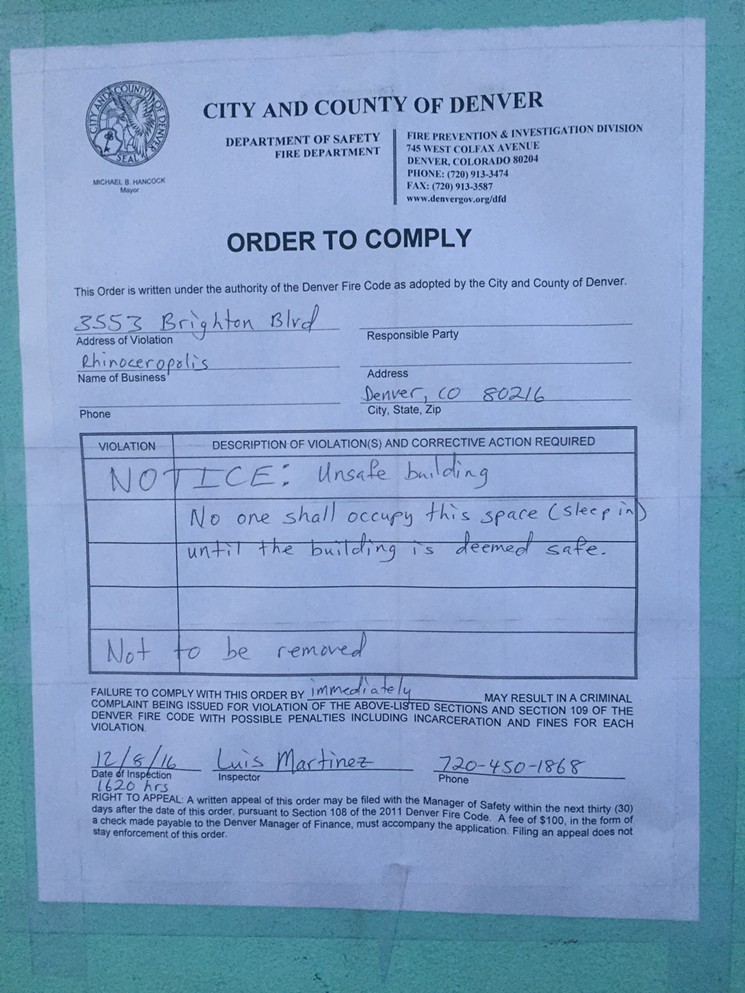

But this time, inspectors had been tipped off that artists were living in the venues illegally. They told the occupants of Glob and Rhinoceropolis that their lives were in danger, and ordered them out immediately. The temperature outside was below 10 degrees Fahrenheit, and Denver officials offered temporary shelter. But the artists declined; they would rather couch-surf than rely on a city that had just booted them out of their homes.

“I never thought it would go down that way,” Golter says now, two years later.

Friends stepped up to house the evicted artists, who hoped to be back in their spaces in a week or two, once the inspectors’ concerns had been addressed.

But this time, city officials slapped the spaces with hefty lists of code violations. Rhinoceropolis could never again be used as a residence, and events there would be capped at 125 people, they said. In order for people to live at Glob, the space would need to be permitted as a home. But in any case, Glob would not be allowed to throw events larger than birthday parties — and those only after extensive repairs that required permits, which could only be secured once an architect had drafted sound plans.

Tenants move their things out of the DIY space Rhinoceropolis at 12:05 p.m. on December 9.

Lindsey Bartlett

Denver creatives and activists quickly organized, accusing the city of waging predatory gentrification in the name of safety through the evictions, and demanding an end to the attack on arts spaces.

In response, the city hosted a panel to discuss safety for artists, encouraged DIY venues to open their doors to inspectors and promised that nobody would be evicted if life-threatening emergencies weren’t discovered. Artists didn't buy it, and a few allies in Denver Arts & Venues took their gripes seriously. Working with other city agencies, they spent the better part of a year trying to find a fix.

While the former residents of Rhinoceropolis and Glob scrambled — some put their belongings in storage, while others left town — Golter sat down with city officials to sort things out. He memorized Denver building codes so that he could better understand what was being said in jargon-cluttered meetings, and hunted for architects and contractors willing to take on a such a small project when far more lucrative contracts abound in Denver.

Architects told Golter that he was facing about $150,000 of work in a building he didn't own. But he was determined to reopen both Glob and Rhinoceropolis. The community threw fundraisers, and a GoFundMe account was launched, raising $13,268. Meow Wolf, the Santa Fe arts collective that plans to open a Denver venue in 2020, gave $20,000 to the outfits — enough to pay some of the bills — as part of its campaign to help DIY spaces across the country.

The donations weren't nearly enough to cover the costs, but Golter labored on with a few friends and volunteers, piling up debt, just wanting to get official permission to go back home. People kept asking when Glob and Rhinoceropolis would reopen. Month after month, he gave his best answer: two weeks.

As the first anniversary of the closures approached in late 2017, the city announced that it would create a Safe Creative Spaces Fund, making $300,000 available to DIY groups that opened their spaces to inspectors and agreed to the fixes. Golter nearly cried when he heard about the fund. That two-week estimate might finally be accurate, right?

Wrong: The city asked for more updates.

Colin Ward and friends welcoming people to Rhinoceropolis for the 2016 edition of Fantasia.

Ken Hamblin III

For a couple of months, work came to a halt. But then Golter kicked himself back into action, motivated now not just by the loss of his home, but by the loss of his close friend.

In all, more than fifteen inspectors have now visited the site at the request of Golter or his contractors; most of them have found new problems that add to the mounting expenses. To address their concerns, Golter has learned to use a jackhammer to demolish a loading dock, installed plumbing, set a toilet and tore down and erected walls.

Fifteen pounds thinner, he's now tired from all the work and weary of hearing the question: When will Rhinoceropolis and Glob finally reopen?

Last week, he thought that the final inspection was set for Friday, November 30, and he was optimistic that the spaces would be found fully compliant — just in time to reopen by the two-year anniversary of the closures. But then the city again stalled his plans: Two more inspectors he had not anticipated still needed to come by and sign off — one for plumbing, another for electrical. (Although Golter's work has already been studied by plumbing and electrical inspectors, nobody bothered to tell him that those visits were preliminaries and that at least another round would be required.)

In 2017, city officials worked closely with the tenant and architect for Rhinoceropolis to come up with creative plans to solve the building’s life-safety and accessibility problems," explains Andrea Burns, the communications director for Denver Community Planning and Development. "After issuing permits for a project, we look to the project’s licensed general contractor to take the lead on seeing the construction through to completion and contacting the city with questions or concerns along the way. City officials – including those who have worked closely with the tenant and architect – are eager to see the venue reopen. In the interim, Denver has gained new options for unpermitted spaces to stay open, a new Safe Creative Spaces Fund for them to draw from, and in the case of Rhinoceropolis, building and fire safety and ADA accessibility for residents and visitors.

These days, the RiNo neighborhood would be unrecognizable to anyone who remembers Rhinoceropolis and Glob in their heyday. A gargantuan new building on the same block dwarfs theirs, and more structures are popping up every day in the area. A few blocks away, corporate entertainment giant AEG is building a large-scale music venue, the Mission Ballroom. The neighborhood is designated an arts district, but creatives grumble that they’ve been bulldozed out of the warehouses they once occupied.

On the garage door of Glob, somebody has spray-painted “Colin Forever,” a nod to Ward and his legacy.

Inside, Golter’s hard work shows. There are now expensive gender-neutral signs on the bathrooms – signs the city requires, despite the fact that these were gender-neutral bathrooms long before Denver adopted that policy. Fireproof drywall divides Rhinoceropolis in half; it looks like the old wall, but it’s thicker. Spray-painted murals, saved from the venue’s glory days, still breathe life into the space. There’s a handsome new wheelchair ramp and a tiny $90 water fountain, a required addition that one day will perhaps save an artist from dying of dehydration.

“In fourteen years, nobody died here,” Golter says. “I would put money on the Cleveland Browns winning the fucking Super Bowl four times in a row before we burned up.”

Golter is still hoping to have the spaces open by Saturday, December 8, but he's not holding his breath. “My best estimate is two weeks,” Golter says, as he has countless times before.

Even if he's able to get Rhinoceropolis and Glob back open and cover all the bills, he knows that won't be a permanent solution for this city's artists. Before the Ghost Ship fire, the landlord had warned that the DIY spaces were on borrowed time, that one day the property might be redeveloped. If and when that happens, Golter will take with him all he's learned about zoning codes and construction, using that hard-won knowledge to open a new DIY project, one that will be a registered nonprofit in a space he owns.

With that vision on the horizon, why waste time coming up with a temporary solution for Rhinoceropolis and Glob?

“They deserve a proper burial,” Golter concludes.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to clarify zoning and permitting issues, to note that the city offered temporary accommodations for the artists evicted from spaces not licensed as residence, and to add that the Denver Fire Department had previously cited the spaces for violations before the December 8, 2016, visit.

The fire department also offered this: "A Type I building is the most fire-resistant building defined by the International Fire Code. The Glob and Rhinoceropolis structures are not Type I structures and do not have anywhere near the same construction or protection. In addition, there was no alarm notification or fire suppression that would be required for a building of this use. The interior of Rhinoceropolis in fact had similar deadly violations to that of the ‘Ghost Ship.' The Glob and Rhinoceropolis occupancies were not designed for people to safely reside in."